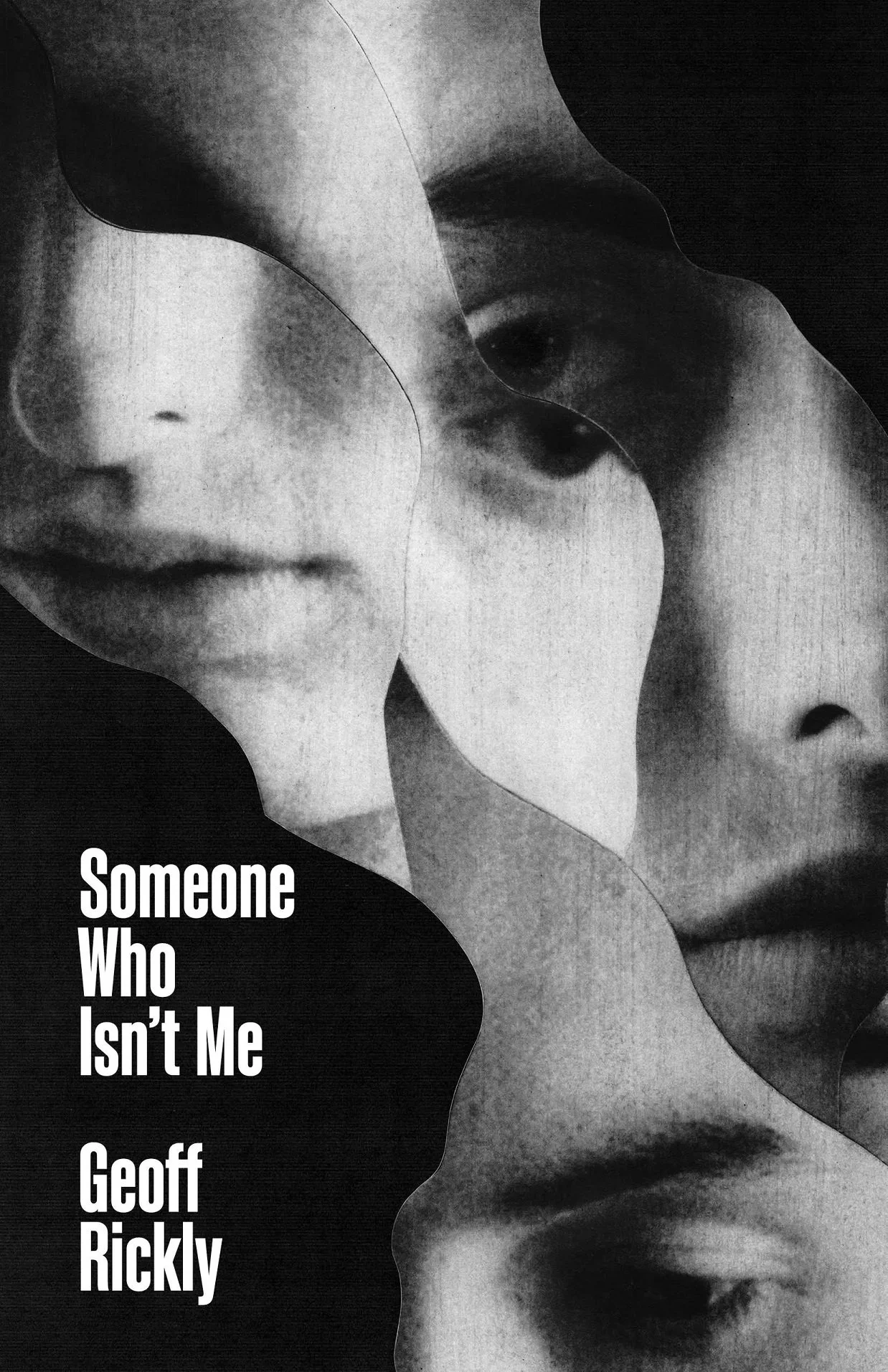

Barrelhouse Reviews: Someone Who Isn’t Me by Geoff Rickly

Reviewed by Mikaela Ryan

Rose Books / July 2023 / 250 pp

Geoff Rickly’s debut novel, Someone Who Isn’t Me, also the debut release from Rose Books, is a labyrinthine journey through memory and time, with an emerging self at the center. The story is based on Rickly’s experience with heroin addiction and rehab at an ibogaine clinic in Mexico. (These clinics use hallucinogenics to bring addictions under control.) Addiction assaults the psyche, and Rickly commits that breakdown to the page, along with subsequent recovery.

Rickly takes us inside the mind of a junkie, Geoff: “my inner violence jumps into the physical world.” As Geoff lives in New York and scrounges for heroin, scenes in the book’s first third alternate: Geoff’s girlfriend Liza breaks up with him, he recounts memories of bandmates (Rickly is the lead singer of post-hardcore band Thursday), he snorts lines in the bathroom at work, and he develops a relationship with a drug supplier, whom he calls “my man.” When Geoff’s condition worsens, he agrees to undergo an experimental drug treatment in Tijuana. The treatment center, which has an on-call shaman, welcomes Geoff and a motley band of patients. Geoff’s peers include two former Marines, a woman who believes her true self is Cleopatra, and a woman with a sweatshirt that says Queen Bitch.

Rickly toys with tenses as Geoff confronts multiple mirrored versions of himself during a series of hallucinatory visions. Geoff’s identity, like all identities, is kaleidoscopic. “Every life is a mirror story,” writes Rickly. While Geoff lies in a hospital bed, ibogaine triggers a surreal psychic landscape: circular cities, circular records, trees. In the vision, Geoff is given a shiny black record that acts as a map. Different grooves unlock different cities and memories he must travel through to process his past. He converses with a fellow bandmate and friend, Steve, and realizes that Steve is just a projection of his own consciousness. “I’m conceptually anchored in your mind as a kind of older brother or authority figure,” the projected Steve explains.

Geoff often refers to himself in second person, third person, collective first person, or as “my reflection,” or “The Observer.” “My reflection makes a phone call, then walks into C-Town on Manhattan Avenue, where he wanders the aisles pretending to look at groceries. When he picks up a can of tomato soup I think, We don’t even like tomatoes.” Later on, he addresses himself in the second person: “You wake up in Detroit. You wake up in Cincinnati.” By using multiple tenses, Rickly simulates the mental instability and disassociation of substance abuse, but also the universal human problem of locating one’s identity. It isn’t until Geoff meets his child self, clad in pajamas, that he finds his essence. The child takes his hand and leads him to ego death. Consequently, the book folds it on itself. It tunnels inward.

The frenetic middle section gives way to a meditative, philosophical—sober—voice in the last third of the book. These three tonal shifts, from reality-adherent, to absurdist, to psychological, bring profound texture to the novel. Moments of wry humor, usually in the form of dialogue, puncture spiritual loftiness. In one scene, Geoff recounts a transformative vision. “’We are everything we love,” he says. “Don’t you see what that means? That must mean we love everything.’” Geoff’s friend replies, “Wow man…They really did a number on you.” Other similarly snappy moments offer levity.

Throughout every segment of Someone Who Isn’t Me, Rickly attends to the novel’s beauty with precise, lyrical, poetic language. He writes that junkies have “soft words to describe violence.” Particular cityscape descriptions stand out. “Outside is a black jewel,” writes Rickly. “Cars gleam against the curb: jet, tourmaline, obsidian, onyx.” The natural landscape receives similar treatment: “Jagged branches of pure white touch down in balletic turns all around us.”

Rickly reminds readers that addiction recovery has its own language of beauty and pain. When you wake from numbness, you see anew. Above all, Someone Who Isn’t Me yearns to sound a pure, clear note. The note is life, “as if our bodies are expensive stereos and life was a song that lasted only as long as we could hear it.”

Mikaela Ryan is a creative nonfiction writer, living in Los Angeles. She received her MFA from Antioch University, where she also worked as an editor for Lunch Ticket. Her work has been published elsewhere in Psaltary and Lyre and you can find her on Twitter @bymikaelaryan.