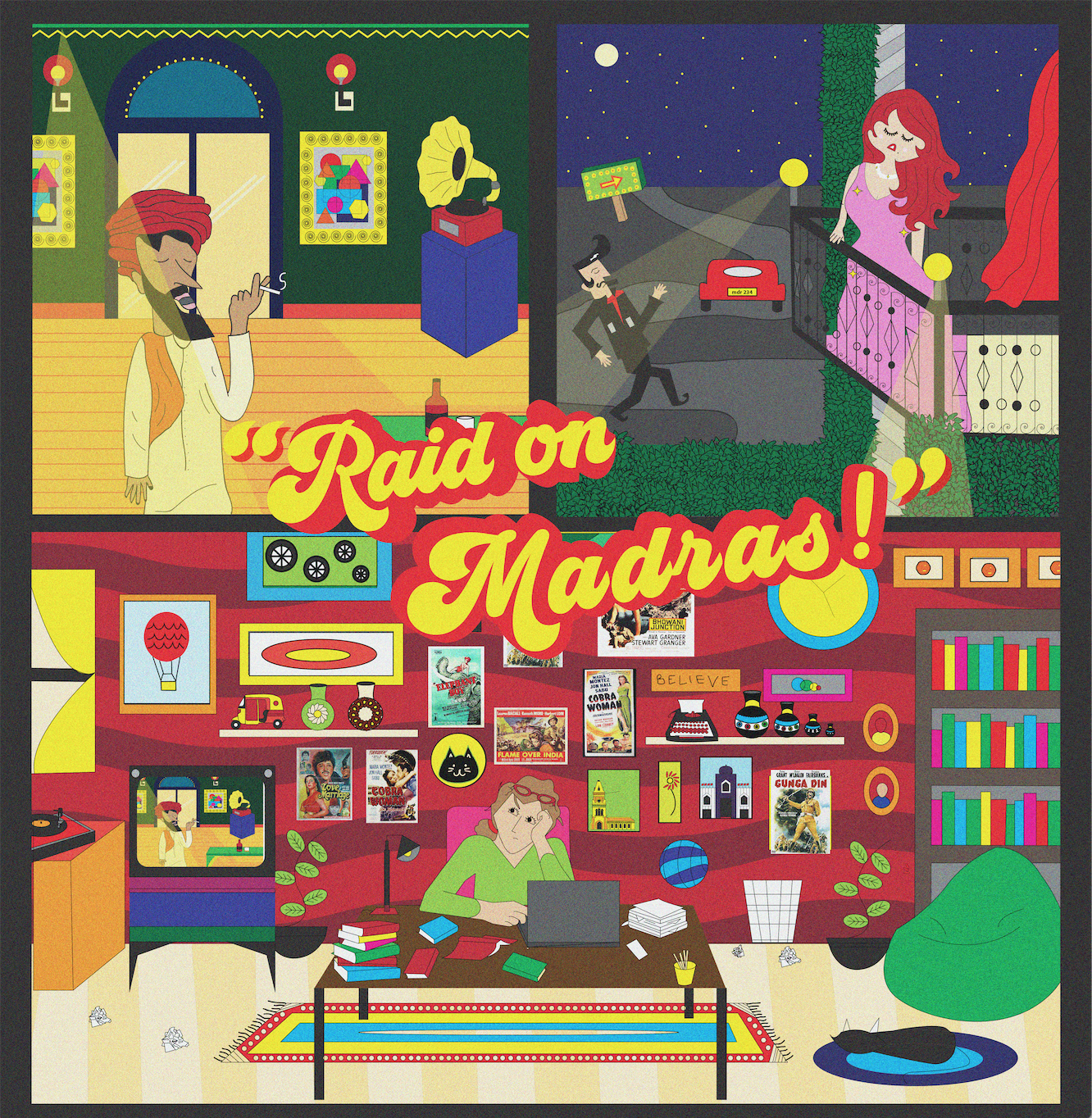

“Raid on Madras,” by Aditya Desai

Artwork by Hafsa Ashfaq

Kalpana had been struck by that Indian butler character, since that late night when the movie was on television, and she’d already seen the Star Trek re-run on the other channel. It was an exemplary quirk of early movie-making that a man with a Turkish name would play an Indian, but then so had a Hungarian and a Russian Jew from New York! We, she wrote later for a now-defunct academic journal, have always been the transparent race, able to not only occupy both minority and majority classes of America, but also represented as such by a carousel of performers whose various ethnic features were deemed “good enough.” Good enough to have dialogue with Mona Laird, the beautiful redheaded star of the film, who Ahmet was playing Indian butler with.

Behind her desk, Kalpana scanned the latest final paper from her class “South Asian History of the 20th Century,” the fifth already today about the global popularity of Bollywood films and how they spoke to the “elemental”, “human”, and “romantic” ideals that societies around the world could relate to. Right now, she actually welcomed her soon-to-be-ex-husband’s text saying he would be moving his stuff out over the week which gave her a chance to lock herself in her office during a feverish semester-end rush. She poured wine into a plastic cup from the bottle she kept on her bookshelf, next to the collected transcripts of Said and Sontag speeches, turned down the lights and watched Raid on Madras for the hundredth time on her laptop, earbuds in.

She knows it well. Well enough that despite being tired, despite being drunk, the story will remain playing in her mind even when her tired eyes block out the screen.

•

The screen, chopped black at the left and right, emblems of a corporate giant that sought to bottle dreams. Dramatis Personae of idols who replaced the deities we know.

The title flashes:

MONA LAIRD and RICHARD THAYER in:

RAID ON MADRAS

It promises to be a daring spectacle. Nestled at the bottom of the post-title cast card:

Ahmet…………………..Rajaji

Her favorite scene was the one that opened the film. The Countess Margaret, gazes from her balcony onto the streets of Manhattan, waiting to hear from her cunning lover Jack Danger, so she may return to India again with him. The camera pans across the tapestry of her socialite couture: cocktail shakers, feather boas draped around oil paintings bought at auction and propped against the side table, the bronze Buddha she shows off at every party, egging friends to rub his belly and ask for luck in love; and there behind it all, stands a man in a turban, holding a silver tray with her martini.

In a visual media seminar where the professor had insisted his course was more interested in film’s forms than the history of its subjects, Kalpana plead her thesis with a two-page analysis about how Ahmet was always relegated as scenery: Take for example how, as the Indian manservant Rajaji, Ahmet seemed to blend into the chiffon curtains and the imported Italian furniture that made up Countess Margaret’s apartment, just one part of her imported luxuries that made her a worldly creature worthy of Jack Danger’s affections. Danger, a desirable WASP specimen with a trimmed mustache and jet black hair, who could so easily pass for Indian himself with an extended day at the beach.

Kalpana’s husband too had a trimmed mustache and jet black hair. He could have played Ahmet in a biopic. But she’s only realizing this now—after the divorce papers have been signed!

•

His real name is Baba Nagul, though for the life of him he can’t figure out why this woman keeps calling him Rajaji. Perhaps she heard it from a predatory market seller in Delhi who told her all Indian men like to be called “Raj,” or maybe Jack Danger had told her, as he often did, striding into her parlor unannounced and spouting off uncited, unbased facts as if they were a prophet’s proclamations.

How she paraded about, blistering with longing pouty cheeks when Danger was off on an adventure. “Just need to quell these blasted dacoits uprising in the Northwestern Provinces, dear love! That’ll teach them to attack our supply lines!” To think he could parade back and forth so quickly!

And about Danger! That for all of her dramatics, those cheeks puffing and grimaced, upset with his bold heroism, when he returned she would still go off with him and dine, while Baba Nagul would slowly clean up their drained glasses of martinis and collect the pillows—thrown about and dampened with her sobs—and arrange them back on the chiffon.

As always, Baba Nagul then turns off the light switch, steals half a finger of scotch from the cabinet, drowns it in a tall glass of ice water, and smokes one cigarette from the box while listening to the only music in the home, an instrumental with no name or composer. He isn’t even where it comes from, as there isn’t even a phonograph in the apartment. But it plays without fail.

Once emptied and put out, he cleans the ash and the glasses, and scurries into his bedroom into a deep sleep, for he knows the morning after Danger will storm off again, and leave in his wake a dame bathing in the musk of last night’s love. And the charade continues day in and out, following God’s careful script.

•

Kalpana’s head begins to nod off, and falls onto notes for a paper she hopes to write about Raid on Madras as an essential critical locus for understanding Hollywood’s brand of exploitative Orientalist revisionism; using the 1943 Japanese bombing of Madras as the backdrop for an adventure-romance.

Her latest find of RoM ephemera was an old behind-the-scenes interview with the actor Ahmet, in full regalia on the set of the film. Above, one can see the large yellow floodlights shining down in a cavernous studio. Behind, the disheveled Manhattan apartment set.

[An interviewer asks Ahmet about his costume] “Is this traditional Indian wear?”

“Probably,” he slurs audibly. “I guess—yes it is. It is designed, uh—the costume department is fantastic.”

“Does it bring you back home? Do you feel comfortable in it?”

[Nervous laughter – from Ahmet, tense, almost maniacal]

“To be honest, no, it’s quite hot in here. I wish I could take this off.”

[A tentative chuckle. From the interviewer, offscreen and unseen] “Like a turtle caught in its shell!”

That line always stung her the most. Such fetishization, she’d written in a draft of the paper, all to sell a fantasy product that itself is implicitly, selling a fantasy of the East! What levels and levels to Hollywood’s excellence!

The paper was to be her opus, her legacy. Put on pause while her annulment took center stage.

But Raid continues.

•

One moment Danger is grumping and ruffling his mustache, but the next he is overjoyed to have Margaret join him in Madras – and of course, Baba in tow, still stuck in his regal white clothes with high collar and the turban, despite the despicable heat. He’d looked to his closet once, when no one was watching – there were only more white robes, more turbans, stored upright and readily wrapped as if custom-made.

Those interminable days, as he was trapped with her stockades of pillows and martini glasses, tumbled into a lavish bungalow close to the sea, all so she could see after Danger, so she no longer had to pout and parade.

But the honeymoon has been cut short.

Baba knows that Madras murmurs about a possible evacuation. Outside, some rabble has taken it as invitation to ransack the bungalows on all sides of George Town. But the Countess cannot leave without packing her ostentation into trunk after trunk as Danger fumes.

“Oh, leave your silly oil paintings, woman! Don’t you know there’s a war going on!”

Baba has never seen the war, though Danger can’t summon thoughts of anything but. He’s come to whisk the Countess away. Good, Baba thinks.

“Oh, but sweet Jack. All I’ve ever known is here. Ever loved.”

But look around you! Baba projects. The bungalow has been made up in pearl-white sofas and chiffons, with draperies blocking out the hot midday sun, only making them all suffer within.

“How could I leave Madras?” she says, collapsing onto the sofa in tears, casting the back of her palm across her forehead. “And what would Rajaji do without me?”

Oh the things I could do without you, Baba fantasizes! Outside he can hear the planes flying from overhead. A window is smashed somewhere down the street.

“Rajaji, sweet Raja. Please come with us.”

Yes, Baba wants to say. Take me with you.

“Oh, just leave the coolie, won’t you!”

Don’t leave me to be skewered by these men.

But he cannot stop himself from speaking:

“No dearest Countess. I will stay behind and lead those bloody dacoits astray! You must go now!”

Danger stiffens. “You’d do that for us, Raja? No wonder my darling has fallen for this land. Some of you people have hearts big enough to contain it.”

A stirring violin crescendos.

•

Though Kalpana is now fully in a drunken snooze, she knows how it will end. She knows that as the last train finally leaves the station, as the bombs descend on Madras and the rabble of bandits closes in toward the palace doors, it will be Rajaji who swoops in to give Danger and the Countess just precious few moments to make their escape. At first the large wooden door he props with a cart of hay will keep them off, but eventually they will break through. He will then whisper sweetly into the ear of his recent acquaintance, Jani the elephant, and implore her to stampede straight into the horde of farmers and herdsmen who are too angry with the young Rajah, sworn under the care of Danger, who has commandeered the last train all for this royal entourage, himself, and his love. By this time Danger will have started the engine, and the train will begin moving out of the station.

Rajaji will chase after the caboose, gaining steam, and just barely latch onto the railing before the bullets rain onto his back. This will be painful, he knows, but it is the sacrifice asked of him.

He will lie there, on the tracks, watching the train escape off into the desert sun, while the screams will descend upon him from behind. He wonders how they could do this to his own countryman, but soon he will be asleep, and wake again in the kitchen, peeling potatoes while outside he can hear the dame and Danger making the same feigned threats to never return each other’s love.

•

“But no,” Baba Nagul says. “This is all wrong.”

This nugget of wisdom, this epiphany—if he so dared to call it that—comes to him while spreading butter on a stale roll, at the next moment he can hears nothing outside the kitchen, the dame and Danger making threats.

“Oh, the boys in the platoon all made fun of me for keeping a foreign memsahib!” Danger says. “Like shackles in the sand!”

“Go ahead, you stupid lout!” Margaret says, smashing a glass. “See if I care while you’re getting your head chopped off in the desert!”

He drops the roll, thunk, onto the counter and strides out to the parlor.

The phantom instrumental has stopped. Danger and Countess Margaret stand frozen, still looking at each other. Danger has her in his arms, a curious look of anger mixed with actorly passion. Baba Nagul walks by, bows, and takes his shawl from the cloak closet. The world, for once, seems to focus only on Baba, as he wraps the shawl about his neck the last of his possessions brought with him from India, and walks out the door.

•

Kalpana, too, wakes in that apartment, in full Technicolor.

But Rajaji the manservant was nowhere to be found. Kalpana walks around the apartment, into rooms she’d never seen, sets that had never been built, calling for Ahmet. Where could she find him if not here? Where else had he existed?

She remembers reading in a biography of Mona Laird’s: the butler had originally been English, but Laird had recently taken an Oriental Tour and had become fascinated with the idea of having an East Indian in her next picture, however possible. Filled with great delight, she called him to afternoon tea, boiling over with questions: “What is it like to ride an elephant? How exactly do you wrap those things around your heads? I think this independence movement you have is absolutely inspiring! Oh, it quite raises one’s spirit, doesn’t it?”

The producers told him his name would be changed to “Ahmet” from Ahmad. It was more European. “You don’t want em to butcher it, do ya?”

Ahmet, singularly-credited, went on to roles in more jungle adventure pictures, even a guest spot on the celebrity edition of $10,000 Pyramid shortly before his death at 58 from complications brought on by alcohol.

That had been the full brunt force of his imprint on the world, which fueled Kalpana in turn. Perhaps it was all for the better that no one had much to say to him once the film reels stopped spinning atop the cameras.

The apartment is empty, with only the beautiful Countess staring from her balcony, upset over Danger, off to his next adventure. Kalpana looks out with her, and even though Ahmet is long dead, she sees Rajaji hailing a cab, his regal white robes unremarkable in a street of leather jackets and stiletto heels, leaving her to contemplate how else to follow him in a world that had never been created.

She leaps down.

•

They, the two, are in the back seat of the taxi. He does not speak nor look at her. She can do nothing but stare, but her mouth becomes too parched to express her decades of close examination.

The car speeds through the city, and out into the countryside. The driver rambles about his son who has run off to join a jazz band in California. “Way out west! That’s where all the riches are!” She doesn’t pay much mind to any of it. It reminds her of when she still had notions of a marriage built on a you-and-me-baby-against-the-world ideal, cut from Danger’s tuxedo tail cloth.

When the taxi stops, Baba impulsively rounds the car and opens the door for his companion. She stumbles out and looks around at the vast tracts of desert. Rock formations jut from the ground. There are cacti. He doesn’t know what to make of this woman, watching her gawk at the open field, not unlike so many picaresque vistas in India.

“There must a palace somewhere,” she keeps saying.

He hadn’t the slightest idea what she was looking for.

“There is an old movie. I wonder if you have seen it?”

He has never seen any films. There is a cinema hall across from his memsahib’s apartment, and he watches the lines fill up. He stands outside in the cold with her coat, while she and Danger view lives more glamorous than theirs.

He has not come this far in life to play servant with yet another lady, forever waiting on him.

He walks in the direction of the setting sun. She runs after him.

Wait, wait! she calls. She keeps addressing him with more made up names. No more Ahmet, no more Rajaji, none of it. He is Baba, and only for himself.

He waves toward the vista. He doesn’t want to speak English to another Indian, they always seemed to poke the greatest fun. He knows numbers and greetings, “best,” “all city,” and “very best,” and he’s already expended that vocabulary. He is compelled to bow with each syllable.

She feels as if she is watching herself, an out-of-body experience. This is not life as it is supposed to be. Perhaps her soon-to-be-ex-husband will reconsider. He won’t be moving his boxes out of the house this weekend. He will unpack each item tidily arrange it back into the closet, onto the kitchen counter, inside the medicine cabinet. Ahmet, Ahmet, she calls.

He keeps walking. She knows she will follow.

•

By sunset they arrive to a clearing, where there is the edifice of a grand palace. A hundred feet away, a small crew stands behind a camera as a train creeps down a track that does not go anywhere. They watch Rajaji, running after the caboose, struggling to hold onto the railing. She tries to pull him, and prop guns in the distance burst smoke—phat phat phat—and Rajaji winces, letting go and withering on the track. In the back, Jani trumpets.

The train halts, and backs, all the way to the palace edifice. Baba Nagul, possessed, bolts down the hill, and Kalpana follows. There is Jack Danger and there is the Countess and look, Jani the Elephant too, all joining the crew, who shut off the lights and retreat behind the grand doors.

Inside, the lights shine down on the set of a palatial New York City apartment, recreated in a California warehouse where it was hotter in than outside.

The apartment looks familiar to her, but differently so. There were stacks of unopened mail, bills her soon-to-be-ex-husband usually handled, donation requests from the university, a couple of wedding invitations from distant cousins whose names she never remembered. They all hang on the refrigerator door now, judging her. She notices the emptied bookshelf, stacks with hardbound editions of their works, which neither her nor her husband ever read in their entirety. At conferences will they have to grit her teeth and praise each other? Passing each other like smiling ghosts?

A noise jolts her. A light bleeds from the hallway in the dressing rooms. She can hear him hissing a monologue in hushed, angry tones, a language that at once sounded familiar and completely foreign. She creeps toward it. Through the crack, she sees the skinny, bare brown torso tugging his robes over his head, and wonders again if familiarity is playing tricks on her. Is this Ahmet, or is it Baba? The quirk of that unknown Indian, his head caught in the collar of his costume, blinded and wriggling around the room, trying to tug it off like a skinny turtle caught in its shell.

Aditya Desai lives in Baltimore, where he is currently teaching writing and revising a couple of novels that he keeps threatening to finish someday. He received his MFA in Fiction from the University of Maryland, College Park. His work has appeared in B O D Y, The Rumpus, The Millions, The Margins, District Lit, The Kartika Review, The Aerogram, CultureStrike, and others, which you can find at adityadesaiwriter.com. You can find him on Twitter @atwittya.

Hafsa Ashfaque is 20 years old and from Karachi, Pakistan. She is a design student at Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, and has been working as an illustrator on book illustrations and commissions since 2017. Her style varies from vector art to hand-drawn illustrations, but her signature style is anything hand-drawn with thick strokes and bright colors. You can find her on Instagram and Behance @hafsaashfaqq.